Topology of Numbers - II

(I will understand how geometry can be used to study numbers using a construction called the Farey Diagram. Chapter 2 of Topology of Numbers.)

Chapter 1 : The Farey Diagram

We want a 2D pictorial representation of rational numbers that displays interesting relations between them.

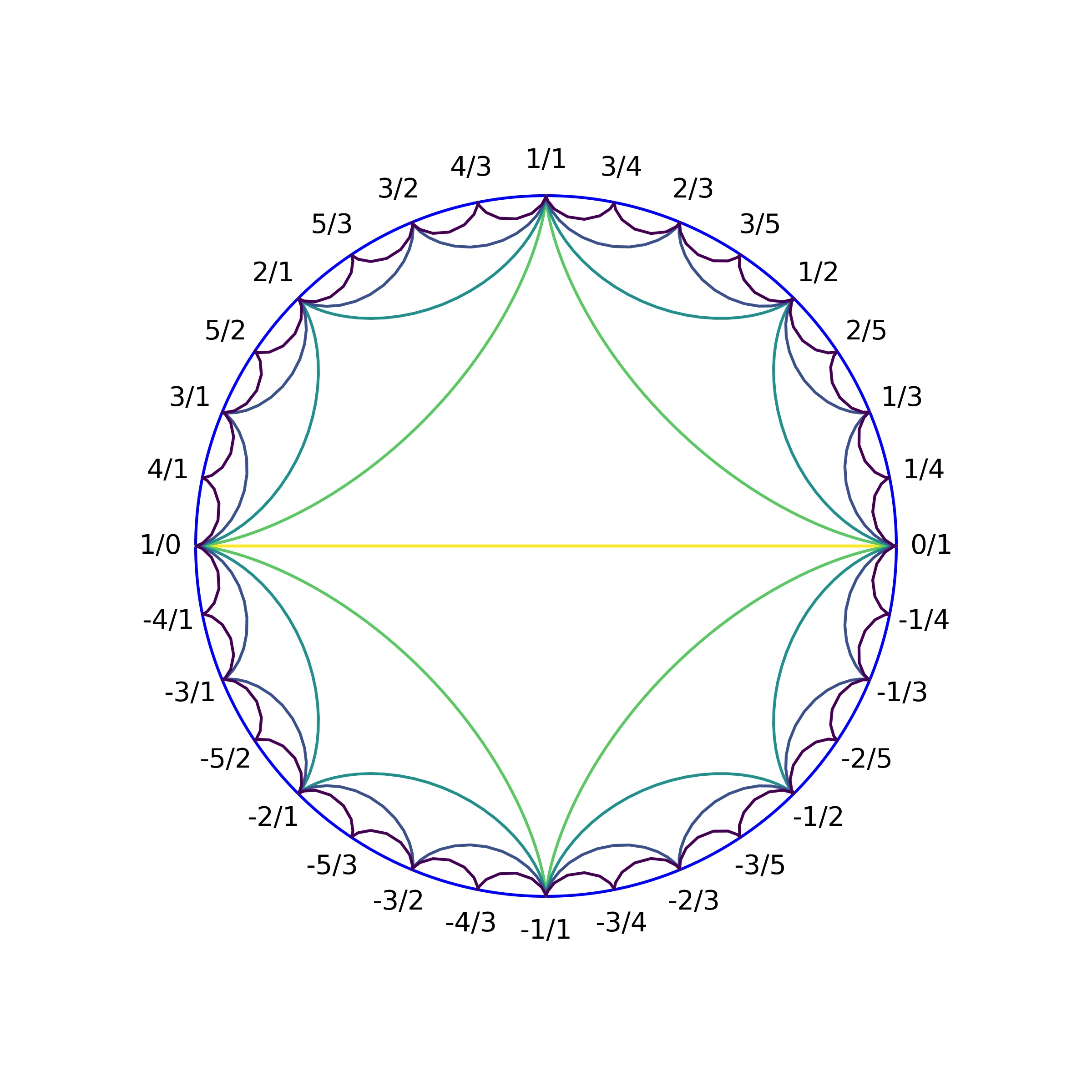

To get started, here is how the Farey diagram looks like

I created this image using matplotlib (repo link). The numbers are generated using a recursive function while the connecting arcs are given by a hypocycloid, which is a curve generating by a smoothly rolling circle inside a large circle. Interestingly enough, the hypocycloids are solutions to the brachistochrone (shortest time) problems for gravity inside a uniform sphere (This might be an interesting calculation for a future post).

Construction of the Farey diagram

We want to represent rationals. Let’s start with \(0/1 \) and \(1/0 (=\infty) \). Define the mediant construction as, given points \(a/b \) and \(c/d\), the mediant is \((a+c)/(b+d)\). We will then write the rational number at the midpoint of the arc connecting \(a/b \) and \(c/d\).

For example, if we start with \(0/1\) and \(1/0\), we get \(1/1\). Then from the pairs \(0/1,1/1\) and \(1/1,1/0\), we get \(1/2\) and \(2/1\) respectively. We repeat this process recursively to construct the upper half of the diagram. The lower-half is given by flipping the numbers about the \(x\)-axis and flipping the sign of the numerator. Note, in this construction \(1/0 = \infty = -1/0 = -\infty \). I have also shaded the arcs to represent different stages of the recursive process.

Thus, we have obtained a representation of rationals on a circle. They occur in proper order around the circle, from \(-\infty\) to \(\infty\) as we go around the circle in the counter-clockwise direction. This way of arranging the numbers has certain special properties as we will see in the following sections.

Properties

To see why the numbers are ordered, we can show the following lemma

The construction is an inductive process. Can we have a criterion for when two rational numbers \(a/b\) and \(c/d\) are joined by an arc? There is one:

Two rational numbers \(a/b\) and \(c/d\) are joined by an arc if and only if \(ad - bc = \pm 1\). This also applies when one of \(a/b\) or \(c/d\) is \(\pm 1/0\).

Note that in our construction, the arcs never cross because at each stage, by the mediant construction, we only create arcs inside the arc of the earlier stage. The above criterion implies that those are the only allowed arcs i.e. any rational numbers which need to be connected because \(a d - bc = \pm 1 \) will already be connected from the construction. This above assertion will be proved later.

Farey Series

Let us restrict to rational numbers between 0 and 1. We start with \(0\) and \(1\), then insert half \(1/2\). Then insert the thirds \(1/3\) and \(2/3\). Then the fourths \(1/4\) and \(3/4\) skipping \(2/4\). And so on.

In fact, if we use a recursive function starting from \(0/1\) to \(1/1\), to generate the numbers, there is a curious observation that the numbers generated are always in lowest terms and are not repeated.

This is how the construction looks like geometrically:

Note that two numbers \(a/b\) and \(c/d\) are connected by an edge, iff \( ad - bc = \pm1 \). The triangles formed by the edges correspond to exactly the function calls in the recursive process.

The discovery of this phenomenon is attributed to Farey in the 19th century. The sequence of fractions \(a/b\) between \(0\) and \(1\) with denominator \(b \leq n\) is called the nth Farey series \(F_n\).

E.g.: \(F_3 = \frac{0}{1}\frac{1}{3}\frac{1}{2}\frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{1}\)

I found a curious fact in the size of \(F_n\). Observe that size of \(F_n = (n)^{th}\) prime number i.e the sizes of \(F_n\) is the sequence \(2,3,5,7,11,…\). This turns out is only a coincidence until \(n = 9 \). \(F_{10} \) has length 33.

There is a second geometrical way to construct the Farey sequence using straight lines in a square.

- Start with a square together with its diagonals and a vertical line from their intersection point to the bottom edge of the square.

- Connect the resulting midpoint of the lower edge of the square to the two upper corners of the square and draw vertical lines down from the new intersection points this produces.

- Repeat the step to connect the new dropped points on the lower edge to the earlier corners, creating a W-shaped zigzag. Repeat with the new intersections obtained.

This process uses the following property of the diagonals of a quadrilateral:

Here, consider a quadrilateral with the given corners. Then the diagonals intersect at the point \(\left( \frac{a+c}{b+d},\frac{1}{b+d} \right) \). This is easy to prove using co-ordinate geometry. Note that the corners of the quadrilateral come in pairs of the form \( (a/b,1/b) \) and \( (a/b,0) \). The new point created by the intersecting diagonals is also of this form. Hence, if we start with \( a = 0, b = 1, c = 1,d = 1 \), i.e. the co-ordinates of a square, and drop verticals from the intersection points of the diagonals, we will reproduce the Farey sequence on the x-axis because of the mediant rule.

The Upper Half-Plane Farey Diagram

The important part in the square construction above are the triangles connecting them. We can change them into curvilinear triangles and obtain the figure below:

In this representation, the vertex labelled \( \frac{a}{b} \) is exactly at the point \( a/b \) on the real axis. We can also expand this for numbers beyond \(0\) and \(1\) to get a represenation for the full real axis. One of think of this as flattened version of the Farey circle.

Relation with Pythagorean Triples

Recall that rational points \( (x,y) \) on the circle \( x^2 + y^2 = 1 \) correspond to rational points \( (p/q,0) \), obtained by connecting this point to \( (0,1) \).

Hence, if we start with the Farey sequence on the real axis and connect it to \( (0,1) \), and look at the intersections to the unit circle, one can show that a quater-turn rotated version of the Farey circle is obtained.